Authors

Dennis Galletta, Kathleen S. Hartzel, Susan Johnson, Jimmie L. Joseph, & Sandeep Rustagi

Abstract

The pervasiveness and impact of electronic spreadsheets have generated serious concerns about their integrity and validity when used in significant decision-making settings. Previous studies have shown that few of the errors that might exist in any given spreadsheet are found, even when the reviewer is explicitly looking for errors. It was hypothesized that differences in the spreadsheets' presentation and their formulas could affect the detection rate of these errors.

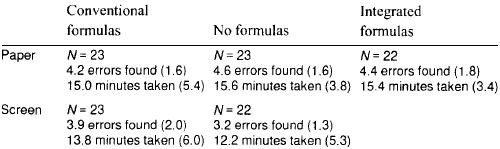

A sample of 113 M.B.A. students volunteered to search for eight errors planted in a one-page spreadsheet. The spreadsheet was presented in five different formats. A 2x2 design specified that four groups were given apparently conventional spreadsheets for comparing paper and screen and the presence or absence of formulas. A fifth group received a special printed spreadsheet with formulas visibly integrated into the spreadsheet—printed in a small font directly under the resultant values. As in previous studies, only about 50 percent of the errors were found overall. Subjects with printed spreadsheets found more errors than their colleagues with screen-only spreadsheets but they took longer to do so.

There was no discernible formula effect; subjects who were able to refer to formulas did not outperform subjects with access to only the final numbers. The special format did not facilitate error finding. Exploratory analysis uncovered some interesting results. The special experimental integrated paper format appeared to diminish the number of correct items falsely identified as errors. There also seemed to be differences in performance that were accounted for by the subjects' self-reported error-finding strategy.

Researchers should focus on other factors that might facilitate error finding, and practitioners should be cautious about relying on spreadsheets' accuracy, even those that have been "audited."

Sample

Subjects working on paper without formulas found the most errors, but also took the longest time.

The next best experimental treatment was for subjects working on paper with formulas.

Subjects working on screen without formulas performed the worst.

Publication

1997, Journal of Management Information Systems, Volume 13, Number 3, Winter, pages 45-63